This Blog has Gone to the Dogs.

In 1997 when I promoted to Homicide, I was introduced to a tool of investigation that was new to me: scent canines. Droopy-eared hounds, low and stable, good for cornering if they were ever to build up speed. Which they don’t. They are slow and steady, designed for longevity.

A special species of canines, these are dogs with jobs.

Ted Hamm, a large-framed, gray-bearded man with an easy smile, was one of the two faces associated with the hounds of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department. He and his partner, Joe D’Allura, started out as volunteers working for the department, offering their services and that of their highly trained scent-trailing canines, 24/7. They eventually earned a contract and were henceforth paid for their work.

Their Story

I wanted to tell their story as a way of recognizing their tremendous service to both law enforcement and to the citizens of Los Angeles County. I recently interviewed Ted with the intent of writing a story. However, it is his story, and the way he told it during the interview was so interesting and compelling, I wanted it to be his voice, not mine. This is longer than my usual blogs by quite a bit, but don’t cheat yourself by skipping it or skimming it; I promise you will find the information revealed in this interview fascinating:

The Interview: Danny R. Smith (DRS) and Ted Hamm (TH)

DRS: Ted, how long did you and Joe work as canine handlers for LASD?

TH: I started with the County as a volunteer in 1989, became a contractor in 2000. I retired in 2015, so about 26 years total. Joe was with the county about 23 years.

DRS: How many call-outs did you respond to with your dogs?

TH: I responded in total around 3,500 times including both Search and Rescue calls and criminal call-outs. About 350 were Search and Rescue. About 750-800 of those criminal call-outs were for homicide cases. Joe had probably about the same number total, because he did a lot of scent lineups that didn’t require me being there.

(Note: A scent lineup is conducted with scent collected from a suspect onto a sterile pad. That pad is spaced out in an open area with five additional pads containing human scent from persons unrelated to the case. The dog is introduced to scent from an item of evidence recovered from the scene, and then asked to check each of the other scent pads to determine if a corresponding scent is present.)

DRS: What was the success rate of the scent canine deployments?

TH: The number of times—not including Search and Rescue—that we literally walked up to the suspect on the street or went to a house where the suspect was located was kind of rare, maybe around 10% of the time (350-400). However, I kept track of what we called “verified” correct, meaning the work of the dog was later proven to have been correct. For example: the dog takes us two blocks from a crime scene and stops, indicating the trail is lost. Investigators later learn through witnesses or a confession that the suspect had fled for two blocks on foot and entered a vehicle where the scent trail had ended. I would log that case as “verified correct.”

As time went by, I would learn more, and be able to better train the dogs and to be able to better understand what the dog was “telling” me. So, with my first dog, my “verified correct” cases were around 25%. That doesn’t mean necessarily the dog was often wrong, just that we could never verify nor disprove. With these first dogs, the number of cases where the dog was proved wrong was around only 2-3%. By the later years our work improved to the point we were doing about 40+% verified, and around 1% proven wrong.

DRS: What was your experience with scent evidence being accepted by the courts?

TH: I testified in approximately 450 cases. One of those cases resulted in a hung jury. It was retried, and the defendant was convicted. There was only one case that resulted in an acquittal, and one other where I was not allowed to testify. The judge in that case had stated he didn’t trust scent evidence.

(That judge was none other than the Honorable Lance Ito, the controversial adjudicator of the O.J. Simpson fiasco.)

DRS: How many dogs did you train and use over the years?

TH: I worked nine trailing dogs (tracking dogs) over the years as well as one cadaver dog—a Labrador retriever—and two “gun dogs,” both border collies. When I refer to a gun dog, I’m talking about a detector dog (generic for any dog trained to find specific items: drugs, explosives, etc.) that is trained to find guns and related items, ammo, expended casings, etc.

DRS: Did you have a favorite?

TH: I’d say there were two favorites: my second dog, Scarlet, a bloodhound, and one of my later dogs, Bojangles, who was a coonhound. Of my nine trailing dogs, all except Bojangles were bloodhounds. Scarlet was an exceptionally sweet dog, but the reason she was my favorite is it was her great work that convinced the department that using the hounds was indeed a viable tool. We went through a hell of a process to prove these dogs. One main point was to prove we could follow someone from scent collected from an expended casing, something nobody anywhere thought could be done. But we proved it indeed could be done. Expended casings were the most common item we used for suspect scent on homicide cases. Bojangles was just a little machine. That damn dog didn’t care where we were or what I asked of him; he did it. We tracked one suspect who was in custody through the interior of a prison to prove his scent was on evidence from an arson case. I was nervous in that environment, but “Bo” didn’t give a damn. He tracked the suspect through the corridors and into an interview room and jumped into the suspect’s lap. On three separate occasions, after we arrived at crime scenes, Bojangles would get anxious to start working (all my dogs loved to work) and began to howl. The suspects in those three cases surrendered themselves having just heard the dog.

DRS: Tell me about the breeding of these dogs you used.

TH: My tracking dogs were all from reputable breeders with histories of producing both champion show dogs and proven working dogs. All of my dogs were from breeders here in California, except Bojangles; he came from Oklahoma. There weren’t many coonhound breeders to be found in California. The cadaver dog and the gun dogs were pound puppies.

The bloodhound is generally held to have the best nose of any breed of dog. They were bred to have those long floppy ears which partially block sound, and loose skin, especially around the face, which partially blocks their vision. Less hearing, and less vision, and bingo, a dog with a little better sense of smell.

DRS: What would you pay for one?

TH: The bloodhounds cost anywhere from $900 to $1800 for a puppy. It then took a minimum of one year to train each dog to where it could be put to work. That would be if I trained five times each week. Less frequent training resulted in a longer time to a finished product. The exception to the price was, again, Bojangles. His breeder apologized for charging $450 which included shipping him from Oklahoma.

Each of my tracking dogs had well over 1,000 hours of training before they went to work. They also were required to pass a qualification test.

DRS: What is the general principle behind scent trails?

TH: Scent is essentially a complex array of chemical compounds each and every human produces and is unique to each and every individual. The mechanism of scent leaving a trail that a dog can follow is that we shed thousands of dead skin cells every minute. Can’t stop it, can’t block it, can’t alter it. These skin cells literally float off of us and settle to the ground. If the weather is calm, the scent path from a person walking down a sidewalk will be around 20-50 feet wide once it settles out of the air, and further if spread by wind or when stirred up by traffic, etc. The odor will be strongest at the center of the scent path and weaker as you get toward the edges. Thus, my dogs would frequently move sort of side to side within the scent path, constantly checking it and sort of bouncing from side to side as the strength of the scent increases or decreases. The person makes a turn, the dog will frequently go a bit past the actual turn (maybe 10 to 20 feet), detect the change in the strength of the scent, and adjust. Which means the dog then makes the turn but slightly past the actual path. Imagine each person leaves a path of these dead skin cells, but imagine they are colored. Each person is a slightly different color. These particles may mix together, but they maintain their own color. So, if three people walk together, their three colored paths will not blend into one mixed up path resulting in a fourth color, but will retain their individual color (or scent). So, the dog can selectively follow one person by the article we present to it before starting the search. A well-trained bloodhound can follow a scent path that is weeks old (vs most tracking dogs that limit out at between four and six hours). I frequently trained on college and university campuses where we would have a person walk around the campus and then we would return days later, and the dog would follow the person we asked it to and ignore all the other thousands of fresher scent paths.

Tracking (patrol K9) vs trailing (hound). Tracking dogs follow the freshest scent trail which is generally made up of ground disturbances. The easiest way to explain this is if you can envision the smell of a freshly mowed lawn. If a person walks across a lawn, each footstep crushes a small area of grass and then carries the scent of the mowed lawn on a small scale. Same with disturbing dirt, leaves, etc. But, these are generic, short-lived odors. So, if the bad guy runs through a park, but 10 minutes later someone else walks through the park and crosses the bad guys path, the tracking dog will switch to the fresher track. Tracking dogs do not use a scent article. Trailing dogs need a scent article that tells the dog what odor they are to find and follow. A trailing dog will stay on the odor path they were given no matter how many people cross over that path.

When I trained with my dogs to do what we called “station ID’s” (because we would usually do them at stations with someone who was in custody or being questioned) I would have the person the dog was supposed to ID reward the dog, not me do the reward. Sometimes a food treat, sometimes ear rubs, sometimes verbal praise, or a combination of the three. So, the dog would expect something when they “found” the person. I would ask the detectives to have the possible suspect seated, and preferably with their hands cuffed behind them, and if possible have at least two other people seated in the room as well. That way the dog has to make a decision which is the right person.

The best time to run a bloodhound is 30-60 minutes after the person took off. The reason is it actually takes some time for the dead skin cells to settle onto the ground. These dead skin cells are finer (smaller) than grains of talcum powder. Also, the sooner you get the dog on the trail, the less time the bad guy has to move around. They frequently would run home or to a friend’s house, hunker down for a while, then move on. The greatest success is getting to the guy before they move on. Homicide cases were the most difficult because there was always a longer delay before we would be deployed, simply because of the lengthy processes that accompany those cases.

DRS: What was the most interesting case you ever worked on?

One case that stands out is the rape of a 12-year-old girl. She was left at home every morning as her mother would go to work. She would get herself up and go to school on her own. One morning, she woke to a guy lying in bed next to her. He was wearing both a ski mask and a “respirator” type mask (the kind as it turns out, used by people working with fiberglass dust), and holding a knife to her face. He raped her repeatedly. She eventually managed to take the knife away, but fearing she would get in trouble, rather than using it on him, she threw it away. He ran off. In an alley adjacent to the apartment building they found a ski mask like she had described. We collected scent from that item and began trailing the scent of the suspect. The trail led us around a long triangle-shaped block and back to the apartment building and to the door of the apartment next door to the victim’s. When the officers knocked on the door, an 18-year-old male answered. At this point, they had nothing other than that the dog led us there to indicate this kid was involved. The detectives asked me what else could be done scent wise to further indicate if the guy was, or was not, involved. I told them they could take him for an interview, and I could start the dog from the location where they take him out of the car. If his scent is a match (to that obtained from the ski mask), the dog would follow him into the building. So, they took him to the station. About 30 minutes later, I went to the station with my dog. An officer showed me where the suspect exited the car in the station parking lot. That was our starting point. Scarlet tracked him into the building, up some stairs, into the detective’s office area, down a hall and into an interview room straight to the suspect. Joe’s dog also tied the suspect to both the ski mask as well as the knife. This gave them enough to get a search warrant which resulted in the discovery of several respirator masks similar to what the suspect wore. The suspect’s DNA was later matched to that obtained during the course of the rape investigation. The suspect pled guilty and was sentenced to thirty years in prison. This one stands out due to the horrific nature of the crime. We were later honored by LAPD, the District Attorney’s Office, the mayor of Los Angeles, and a state Senator.

Another was a quadruple homicide in Pico Rivera. A family was murdered. There was an 8-year-old girl who was brutally raped before her death. I collected scent from a variety of items of evidence. We started my dog, “Knight” and he led us over the back wall of the house, through the neighbor’s backyard and out onto a street. He took us down the block and up to the front of a house, around to the back of that house, and then back to the front door. Knight then crapped on the doorstep. That was something he did with some regularity, in a way of identifying a find. The deputies wanted me to keep working the dog to see if the scent went anywhere else. So, I restarted the dog, and he took us further down the street, but he was acting like the scent was weaker. I learned from this case that once the dog takes us to a house, we don’t do any more work until that location is checked out. We went back to the house where Knight had crapped, and the officers ended up recovering property stolen from the crime scene at that house. The suspect was identified, and the case solved. One reason this case stands out in my mind is I am reminded of it with some regularity by nightmares about the murdered family, and the horrifically violated and murdered little girl.

DRS: Were you or any of your dogs ever injured or in peril?

TH: Injuries to the dogs were few and minor. Most common was burned feet from working in hot weather. I was knocked off my feet by one of my dogs on a search and dislocated my elbow. I suffered a couple of sprained ankles. In peril? Well, that one is up for debate. We did get shot at from a distance twice. I received numerous threats to both my life and my dogs’ lives. On one homicide case, we tracked the suspect around several blocks but never got a “hit” on a house. The suspect was later apprehended. In his statement, he said he had watched us from inside his house as we searched and had decided that if we were to try contacting him, he would open fire through the door. This was one occasion I was glad the dog hadn’t identified the house.

DRS: Do you still work with dogs, or train dogs (or their owners)?

TH: As much as I miss the work, which I really had a passion for, the only dogs I now train are my own pets. I do still have the last bloodhound with me, and I occasionally train her to make sure she still works well just in case something big comes up and my services are called upon. Once she dies, that will be the end of that. I do still get called to court to testify as an expert witness.

DRS: Do you maintain a website or have a business you would like to mention?

TH: No, but I’m happy to speak with anyone about the dogs, the training, or whatever. I can be contacted via email: tedhammk9s@gmail.com

DRS: What is your favorite part of working with dogs?

TH: My favorite thing about working with the dogs was constantly being shown that they could do such amazing things with their noses. We could follow and identify suspects from scent collect from bomb fragments, incendiary devices, shell casings, items that had been “sterilized.” We worked many long days on the Anthrax letters for the FBI after they had been sterilized. But that is another story, especially if you like conspiracy theories.

Something I’d like to add. I taught my dogs to say “No.” Basically, all handlers (when I started) would give their dog something to smell, then tell the dog to go to work. But we found that a fair percentage of the time, if there was no scent match, the dogs would take a false trail. Because the dog would think it was always his job to follow some scent. It sounds simple enough, but we had to teach the dogs that if there was no scent trail right where we gave them the scent article, they were to just stand still. If there was a match, then (and only then) they were to take off and follow. An example: I got called by Arson/Explosives and they wanted to know if my dogs could get scent from burned Molotov cocktail fragments. It was a first time for such a request and I had never thought to try it in training. But, I told the investigator we can try, because the way I trained my dogs, if there wasn’t any scent on the items, the dog wouldn’t go anywhere. Went to the scene, collected scent from the fragments, and the dog followed a scent trail to a house nearby. The resident confessed as soon as he heard that a dog had tracked him from the arson scene.

To back up our testimony, anytime we worked on something we had never before encountered, we would then do a number of training sessions where we would use the same or similar items for scent to prove it wasn’t a one-time fluke. To this day, nobody knows exactly what “scent” is, but the dogs know and that is all that really matters.

I Believe I Speak for Many

Ted, I want to thank you for your great service to LASD and the citizens of Los Angeles County and beyond. Thank you also for this interview. I think people will find this story very interesting on a number of fronts.

My Final Thoughts

As a homicide detective, I walked many miles behind Ted Hamm and his dogs. Not near as many miles as Ted and Joe, but more than my fair share for a guy in wingtips and a tie. Sometimes I would think, “Ted, you’re killing me,” but never say it. Ted is ten years my senior, Joe about my age. Both had the stamina of marathon runners.

There were times when the trail abruptly ended. There were times when the trail ended at the home of a suspect or an associate thereof. There was a time, as Ted described in another story, when a dog followed a suspect’s scent trail through Compton Station and jumped in the suspect’s lap. Ted looked at me and smiled. “I think that was a positive I.D.”

The best part was that the dogs were always happy to be there, working, and honestly, so were their handlers.

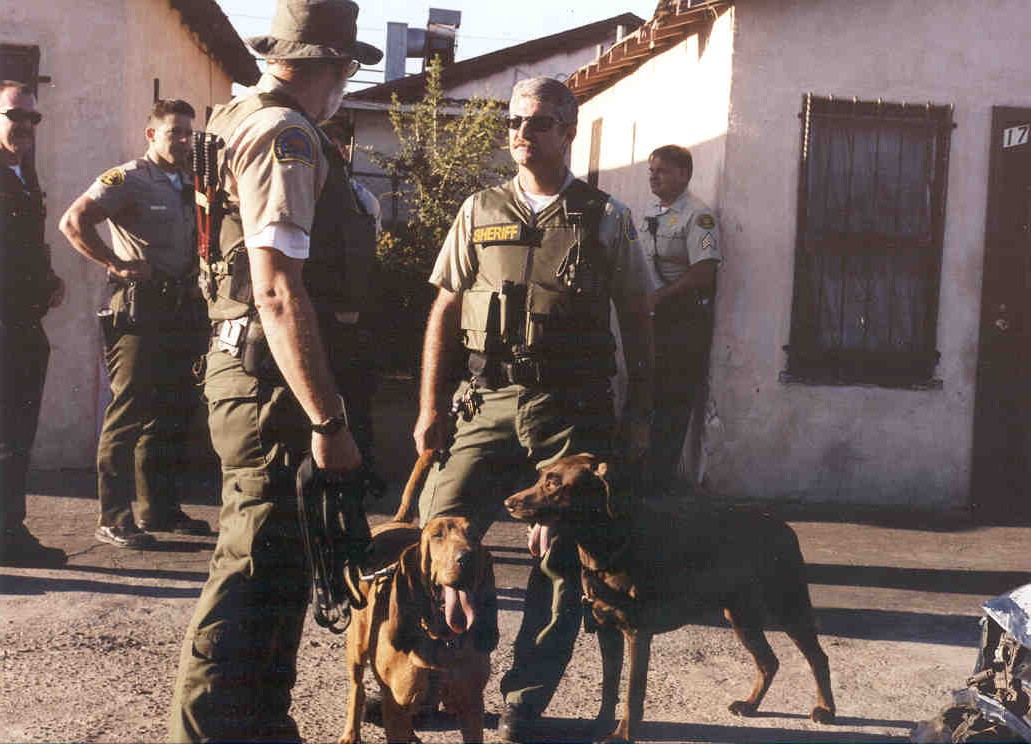

Ted and Scarlet, Joe and his dog, Riley

Ted and Scarlet, Joe and his dog, Riley

* * *

Thank you for reading my blog. I hope you will share it with your family and friends.

Great interview Danny of a great man. I like you have worn the soles off my shoes following Ted, Scarlett and Knight through the streets of LA County. Ted and Joe provided an excellent tool for us to help with our cases. The memories of those guys , their dogs and the good ol’ STU-100 will forever me etched in my memory!

Thanks, Paul. Good memories for sure. Hope you’re enjoying retirement, partner.

I remember a murder on 117th street and the dog led us right to the middle of the projects across the street. It was amazing to watch the dogs work

A murder on 117th Street? No way! lol. Thank you, Robert.

Thanks DRS

Brought back memories of many street hikes in the middle of the night searching for the bad guys. Good job by both you, Ted & Joe and the numerous canines involved.

You bet, Bobby. Thanks for reading and commenting. I look forward to seeing you soon.

Very interesting and thank you for this blog. I really enjoy reading about working dogs. They are so intelligent.

Thank you, Jody. I really enjoyed writing about them!

Great interview. And I ditto all that has been said. Grateful am I to have you all looking out for the rest of us (sometimes) dumb asses! Truly, thank you for your efforts on our behalf. As an avid dog lover and oft-time dog rescuer, I salute both man and canine.

Thank you, Jeanne. I too am a lover of dogs and I was always a big fan of the working dogs. It was fun doing the interview because Ted is a great guy who is obviously passionate about what he does.

Your service is amazing history. Thank you for all the dedicated and hard work over the years. I would love to read more.

Most sincerely,

Sarah

Thank you, Sarah. I hope you do read more. There are quite a few stories in the archives, and of course, my books are available everywhere.

Thank you,

Danny

Great job Danny. The way you weave these stories makes one long for the days when you could put on your gun belt and go out and do some real police work. The interview with Ted is outstanding and very informative.

Thank you, Moon! I really appreciate the kind words and feedback! Danny

Loved his story about the dogs. Very educational.

Thank you! I enjoyed writing it. As much as I worked around the dogs when I was on the job, I learned a lot interviewing Ted. He is a great man and dog trainer.

Thank You. Great story. As a dog lover myself i find the scent stuff fascinating. My miniature schnauzer thinks he is a tracker, and is fun to watch . Love your blogs.

Thank you! Fascinating is a great word to describe watching dogs work. Thanks for the kind words and for reading my blogs! Danny

Brings back many memories. Using dogs was a new in our day. Everyone was learning.

As a K-9 sergeant, I occasionally worked with Ted and Joe. They worked independently of my assignment at Canine Services Detail. They were still volunteers back then.

Good men, good hounds……

Loved this one!

Thank you, Mike!

Judge Ito is ignorant. Only a fool would fail to see the reliability of a dog’s nose. There’s a reason they’ve been using dogs to track animals for centuries. A dog’s nose is good enough for our Tier One special forces to rely on with their lives on the line, but not for Ito in the courtroom. What a dumbass. A human being is just another animal. The dog has no agenda or predjudice. It appears Ito does.

Yes, indeed he is a dumbass. But, just in case someone missed that part about him from the OJ trial, it’s good to point it out. lol. Thanks, partner.

Right on. I preach a line from your comment…”The dog has no agenda or prejudice.” I might add they also have no ego. I was a lucky man to have worked so many years with a canine(s) for a partner.