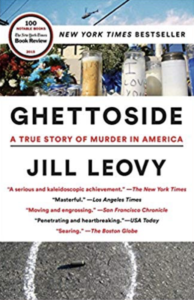

I just finished reading New York Times Bestseller Ghettoside: A True Story of Murder in America, by former Los Angeles Times reporter Jill Leovy. It is the story of homicide in South Los Angeles, more specifically the seemingly endless epidemic of blacks murdering blacks. It is provocative, brutally honest, a story I believe should be read by every cop.

I just finished reading New York Times Bestseller Ghettoside: A True Story of Murder in America, by former Los Angeles Times reporter Jill Leovy. It is the story of homicide in South Los Angeles, more specifically the seemingly endless epidemic of blacks murdering blacks. It is provocative, brutally honest, a story I believe should be read by every cop.

To write the book, Leovy embedded herself with LAPD’s South Bureau Homicide. She focuses primarily on the work of Detective John Skaggs, a man of exceptional talent who is committed to working in the toughest of neighborhoods and solving the murders that plague them, against all odds. When the son of an LAPD officer is killed, Skaggs gets the case. I won’t give more of the book away, but I can tell you that the story will keep you up late and that you’ll close the back cover sooner than you had hoped, and perhaps with a heaviness that you hadn’t expected.

In our initial contact, Ms. Leovy asked if we had ever met, stating that she used to attend Sheriff’s Homicide Wednesday meetings. We figured out that she had done so starting the year I retired, so we hadn’t. However, my good friend, Mark Lillienfeld, a highly respected, recently retired L.A. Sheriff’s Homicide detective, gave her the highest praise any cop could ever afford a reporter: “I knew her. I liked her. I had a good (working) relationship with her and always trusted her.”

I was honored to interview Ms. Leovy for this blog, and the following are highlights of that interview. To condense our discussion to a manageable length, I have necessarily paraphrased some of her answers.

See this #AmazonGiveaway for a chance to win: Ghettoside: A True Story of Murder in America (Kindle Edition). https://giveaway.amazon.com/p/96c092b29dde4d25 NO PURCHASE NECESSARY. Ends the earlier of Aug 13, 2019 11:59 PM PDT, or when all prizes are claimed. See Official Rules http://amzn.to/GArules.

DS: Tell us about yourself.

JL: I was an L.A. Times reporter for twenty-plus years. I had come from smaller papers, as most reporters do, and I had covered a lot of beats—education, city hall, those types of things—went to Mexico for a while, and then I was assigned the police beat which I held from about 2002 to 2008.

DS: Had you requested the police beat?

JL: I had, and I’m not entirely sure why. Most reporters do that (request to cover the police beat) early in their careers, and I was sort of mid-career. I was on my way to do other things when my editor asked if there was anything I had in the back of my mind. I told her I had always wanted to cover cops, and the next day she had me assigned to that beat.

DS: Was it during that time that you wrote Ghettoside?

JL: No, during that time, I covered the police beat as a reporter, I wrote a blog for the paper called The Homicide Reporter, and then after that, in 2009, I took a leave of absence to prepare the book so that I was doing that independent of the paper. That is a common practice, similar to a professor sabbatical.

DS: What gave you the idea to write Ghettoside?

JL: The syndrome of mortality from urban violence is one of the strangest things I ever covered as a reporter. It is complex and difficult, and very poorly understood, and the reporting of it, previous to mine, (seemed) stuck in a forty-year-old rut. I also think the one thing that was different to my approach is that from the very beginning, it struck me as mysterious. One of the things that I think is hard about this subject matter—and I think it’s often hard for cops—is that people don’t think it’s mysterious. They’ve read about it in the paper and they know what it’s about, and they can kind of just shrug it off because it’s not that interesting. And I didn’t think that. I thought it was very interesting, and there’s no reason for it to be the way it is. It’s a strange, mysterious, fascinating phenomenon, and I just got very interested in it and very puzzled by it. And, of course, it’s very compelling.

I used to work with the CDC (Centers for Disease Control) when I did mortality statistics, trying to understand homicide, and the internal parts would leap out, the racial disparities, the gender disparities, and I felt these things are poorly understood. One of the statisticians had told me once that she had provided the data of homicide mortality to a gang intervention worker, and when she gave him the death data for that 18- to 28-year-old group, the man cried, obviously rattled and shaken by hearing the statistical contours of the problem. I related to that; it just knocks you over, it’s so strange and disturbing.

DS: I was surprised by some of the statistics in the book.

JL: My research of homicides in L.A. County during the nineties, when you were a homicide detective, indicated that the death rate for young Latino men was one-fourth the rate for young black men. And you know South L.A. as I know it, that it is one of the most integrated settings you can find, as far as black and Latino people, and there are plenty of Latino gangs also. So the idea that they (Latinos) die so much less frequently than black men, blew me away. It doesn’t fit with the conventional ideas about homicide. If you blame poverty, well, everyone there is poor. If you say it’s because of gangs, there are gangs everywhere. Nothing quite fits with the numbers.

DS: Did you ever find yourself in a dangerous situation while spending time in South Los Angeles conducting research for your book?

JL: I think the only thing that really concerned me was being struck by a stray bullet. One of the officers in the book, Sal La Barbera, once had a homicide scene where the body that remained on the road was hit by a stray bullet while he was investigating. He later would have to explain the “extra” gunshot wound that occurred after death. There were times when I would be speaking with young black men, gang members, and they would ask if I was afraid of them, or afraid to be there in the hood. I would ask who has more reason to be afraid on that street corner, me or them? They would always say that they had more of a reason to be afraid because if a white L.A. Times reporter got shot, it would be all over the news, but if they were shot, that wouldn’t be the case.

There was something though that would change when I would be away from it for a few weeks, almost as if I would lose some of the intuition, or the compassion, and they would sense it. I got used to it and knew I would have to run into some walls for a while until there was some intimacy that would breakthrough. There is something about being there—and this is true for the cops, as well—you’re the one who’s there at two a.m. on a scene that’s not going to appear on any news, but you’re one of the few who care about it and are showing up for it. I think everybody kind of responds to that.

DS: I don’t recall the media covering much of anything that happened in South L.A.

JL: T.V. news always had those contractors who kind of buzzed around and covered some of it. I had covered a trial at Compton court, and two years later, I contacted the clerk of that court to get a transcript as I prepared my book. The clerk told me she knew exactly who I was, and she told me I was the only reporter she had ever known to cover a trial there. She remembered me.

DS: If I understood your thesis in Ghettoside, you attribute much of the killing among blacks in South Los Angeles to be the result of it being a lawless environment.

JL: I would say the conditions are multilayered, but that is the essential one. I feel like one of the things Ghettoside is trying to accomplish is (to get across the idea that) a lot of the social science is too reductive and simplistic, and statistic-based. Anyone who has been on the ground in these environments understands that it is just too complex and interwoven. The impunity part is a big deal; where you have impunity, you have a high rate of homicide.

In black communities in L.A. County, I would say some of the attendant conditions are immobility—people are staying in these neighborhoods, generation upon generation. There’s a way that low-income black people live that is very networked, where everyone has a lot of extended family, and there are “play cousins,” and a lot of lateral relationships wherein they are relying on each other. I think a lot of wealthier people in suburbs barely know their neighbors. Those are kinds of conditions—all over the world—that lend to an environment of homicide.

As an example, domestic violence murder in the U.S. is thought to have declined precipitously over the last forty years. As best as the people who have studied it can determine, one of the reasons for that is the escape. Lethally abusive relationships tend to take a while to reach that catastrophic point; the murders tend to happen after seven to ten years of abuse. Up until the mid-seventies or so, you had these high rates of domestic homicide, and there were murders both ways, meaning some of the instances were women killing their abusers. After the age of divorce, and after the age of women working, the domestic violence murder rate really started to drop off. What sociologists concluded was that relationships weren’t lasting as long, and women were leaving before abusive relationships were reaching that catastrophic point.

That’s a great lesson about homicide in general, that when people can’t escape, things are going to heat up a lot more and you’re going to have a lot more homicides. So with people who have very low income, who are stuck in these big housing projects of stucco apartments with barred windows—they move around a little, going to San Bernardino or Rialto or whatever, but they’re not highly mobile. They can’t really get away, and that contributes a lot to making it a high homicide environment.

There’s also a lot of history. There are stories I’ve read when I went back into the archives of the L.A. Times, the era of when many, many black migrants were coming from Louisiana, East Texas, and Oklahoma to parts of L.A. People noticed—at that time—that these people had really had a very different experience with police than what we’re used to, that they were used to police beating them up, and so you have that legacy of distrust. And that really wasn’t very long ago.

That matters because building the law is a historic process, and it’s complicated. Think about law enforcement in the U.S., under Jim Crow in the south before five million black southerners moved out, think about Chicago in the 1940,s, in Baltimore and L.A. in the 1960’s—I just don’t think you can point to an era where there were really all the conditions present to sustainably build law and build a system of legitimacy among African-Americans. So getting people into prison for murder in black communities was always fraught, cases being downgraded to manslaughter or cases not even being filed. That creates a vicious cycle where you get less cooperation from witnesses.

But it’s very subtle, because some things do get prosecuted, and some don’t, such as the low-hanging fruit that I mentioned in my book.

Next Week – Part II:

“It is really corrosive for police officers to think their work is meaningless. I think it is a hazard of the job that dogs people. What made Skaggs so successful is that he had a really clear idea of what he was doing and why he was doing it.”

* * *

DON’T FORGET — ENTER TO WIN A FREE COPY

See this #AmazonGiveaway for a chance to win: Ghettoside: A True Story of Murder in America (Kindle Edition). https://giveaway.amazon.com/p/96c092b29dde4d25 NO PURCHASE NECESSARY. Ends the earlier of Aug 13, 2019 11:59 PM PDT, or when all prizes are claimed. See Official Rules http://amzn.to/GArules.

* * *

A GOOD BUNCH OF MEN

DOOR TO A DARK ROOM

DOOR TO A DARK ROOM

ECHO KILLERS

ECHO KILLERS

THE COLOR DEAD

THE COLOR DEAD

Death after dishonor

(Coming September 2019)

“The leadership reflects a political environment where the public does not value the function of solving crimes.”

I think the public truly values Law Enforcement’s efforts to solve crimes and punish offenders….. so long as it does not involve them or their families. Takes a special person to turn in their friend or relative for a crime.

The so called, “Leadership”, has one agenda….. look good so we get promoted, re-elected or otherwise benefit personally and professionally. That is a core problem and is truly tragic.

When we worked, our goal was to fill the back seat, make the jailer work all day or night, and let everyone know that the Good Guys were out and about. Working. We were either loved or hated, depending on who you spoke to. I would do it again in a minute.

Leovy seems like an interesting person to talk with and definitely has some great insight. After seeing it firsthand, my thoughts regarding the death syndrome in South L.A. were that the majority of the people are apathetic…. they do not place the same value on human life as others. Uneducated, unmotivated, immobile, dependent on a broken system of welfare and healthcare, knowing helplessness and hopelessness for generations….. killing and getting killed gives them something to do and is any easy escape from a horrible way of existing.

I agree there are many factors, and it is complex. Fatherless boys is another. The most interesting part for me is the impunity she speaks of. I think there is a lot to it. The book is fantastic–a must-read in my opinion, especially for cops.